My Ebenezer

Albania

I have shared a number of light hearted stories recently, but today I would like to share about a time in my life that changed me forever and made me the person I am today. Quite a few years ago my life was miserable. It was miserable because I made it that way. Bad choices, runaway pride, and a total disregard for God’s leading in my life sent me into a tailspin that damaged everyone and everything in my life. This story, however, is not about failure—it is about redemption and God’s grace that is beyond my ability to understand. All I can do is accept it and be eternally thankful. An Ebenezer is a marker in life. It signifies that what was before has been replaced by what is after. My Ebenezer came in a remote mountain village during an AERO Projekt in Albania.

I have shared a number of light hearted stories recently, but today I would like to share about a time in my life that changed me forever and made me the person I am today. Quite a few years ago my life was miserable. It was miserable because I made it that way. Bad choices, runaway pride, and a total disregard for God’s leading in my life sent me into a tailspin that damaged everyone and everything in my life. This story, however, is not about failure—it is about redemption and God’s grace that is beyond my ability to understand. All I can do is accept it and be eternally thankful. An Ebenezer is a marker in life. It signifies that what was before has been replaced by what is after. My Ebenezer came in a remote mountain village during an AERO Projekt in Albania.

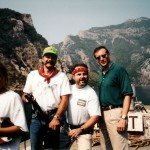

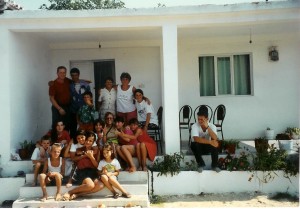

I decided to participate in the project because that is what I had always done during my summers for several years before. I knew I was running from God and not living for Him, but I still felt compelled to join a JESUS Film team. When I got to Albania I was assigned to be a team leader as in the past. My new team of Albanians had heard about me and were very excited to be on my team. What they didn’t know was that I was secretly struggling in a constant battle with God. And I was losing!

One night in our followup village—see earlier posts on what that entailed—I found myself sitting alone on a stone wall overlooking a deep valley surrounded by tall mountains on three sides. As I looked down the valley I could see the valley we were in flowed perpendicularly into a larger central river valley. The sun had set and my team was in our hosts home preparing a meal. I sat on that wall with my feet dangling over a cliff and my back to the courtyard of the house. I was in tremendous turmoil that night. I had run as far as I could and had no where else to go. I felt as if God had finally gotten a hold of me by the scruff of the neck and was giving me a good hard shake. After months of rebellion I began to pray in earnest to the God I had always wanted to serve, but had recently turned my back on.

Tears flowed and gut wrenching heart ache gripped me as I began to acknowledge my long list of sins, and ask for forgiveness. I know I was talking out loud to God and I soon felt His presence flow over me in an unexplainable peace as I realized that true to His word He had forgiven me. At one point my Albanian co-leader, Lawrence, came out and asked if I was all right. My team as it turned out knew something was wrong with me pretty much from the time we went into the villages, and was at that time in the house praying for me. I turned to Lawrence and told him I was getting my life back with God the way it should be. He told me they were all praying for me and left me alone again. I spent a full two hours sitting on that stone wall, but the Ebenezer was quickly to follow.

Lawrence came out of the house and told me that our host, Avni, had asked if I could go out and take photos of his son Mustaffa who had brought their sheep in off the mountain for the night. Mustaffa and his flock had spent several days and nights up on a high pasture and had returned to the village. I grabbed my camera, feeling like I belonged on this team for the first time since I had been with them. It is amazing what God’s grace and forgiveness can do. It takes you from a groveling failure to an empowered warrior for Him.

When I arrived I found the sheep had been first sequestered in a pen surrounded by a tall hedge of thorns tightly woven together to make a wall. Inside the pen was a stone building that had walls built up to about eight feet tall. Mustaffa was sitting on a low stool blocking a very narrow door into the stone building. The door itself was only about two feet wide. Mustaffa propped his foot up against the jam and I took photos of him and his sheep as they one by one went passed him into the stone building. I walked around within the outer pen with sheep brushing up against my legs, but paying absolutely no attention to me, and I snapped photos from different angles with Avni and Lawrence looking on.

When I arrived I found the sheep had been first sequestered in a pen surrounded by a tall hedge of thorns tightly woven together to make a wall. Inside the pen was a stone building that had walls built up to about eight feet tall. Mustaffa was sitting on a low stool blocking a very narrow door into the stone building. The door itself was only about two feet wide. Mustaffa propped his foot up against the jam and I took photos of him and his sheep as they one by one went passed him into the stone building. I walked around within the outer pen with sheep brushing up against my legs, but paying absolutely no attention to me, and I snapped photos from different angles with Avni and Lawrence looking on.

After a time it suddenly dawned on me that Mustaffa was making noises with his mouth that sounded like chirps and lip flaps and clucks and clicks. I watched amazed as he made different sounds and specific sheep moved forward in line and went through the door. At one point he made a series of sounds and a sheep started through the door. Mustaffa pushed the sheep away and made the same sounds again and a sheep three sheep back in line moved forward to the door as Mustaffa moved his leg for it to pass. It was then that I realized that these sounds were actually the names of the sheep and each sheep had its own name and came into the fold in a specific order. This just about knocked me off my feet. These sheep didn’t have names like Fred, or Mary or Peter. They had names that consisted of lip and throat sounds from their shepherd. And this shepherd knew his sheep by name.

One by one the sheep entered in turn. Occasionally Mustaffa would milk a ewe that would come through the door before allowing it to pass through. When the last sheep entered the stone building Mustaffa stood up and said he was missing a sheep. Tears began to run down my cheeks in the dark. This was the parable of The Lost Sheep that Jesus told right out of Luke chapter fifteen. And I was living it! I thought of the verse that said, “My sheep know my voice,” and I had just observed that those sheep cared nothing for Lawrence and I, but only for the voice of their master, Mustaffa. He then asked Lawrence and I if we would go into the the night with him and find his lost sheep.

We went out, Mustaffa called out using lip and throat sounds again—different than any of the other sounds he had used earlier for the other sheep. After a while with no success, Mustaffa turned to Lawrence and I and said, “This sheep will come back on its own. It has done this before.” He then turned and walked back toward the house.

At this point the last bastion of my pride collapsed, and I fell to my knees in the dark and bawled like a baby. Lawrence knelt beside me and put his arm around me saying nothing. I finally said,”I have been running from God for a long time. God has given me this experience to show me His unending love. I am that lost sheep.” Lawrence simply said he and the rest of team knew I had been struggling with something since the day they met me, and they had been praying that I would allow God to work in my life.

When we got back to the house my team and the family came and embraced me. Even though they didn’t know any details they could sense that I had had a great burden taken off of me. Mustaffa brought the sheep dogs into the house, which was not the usual custom, so that they would not harm that one sheep that was out. The next morning, just as Mustaffa said would happen, we found that lost sheep quivering, cold and full of stickers at the gate of the hedge of thorns, but otherwise unharmed.

There was my life before that night, and there has been my life since that night. My Ebenezer. I have been so thankful for how God allowed a Bible story to come to life for me when I needed it the most. That special time has allowed me to live my life confidently, and whole-heartedly for God. I’m not perfect—I’m far from it and I still make a lot of mistakes, but I know God loves me and has a wonderful plan for my life, and that life doesn’t include going one second with unconfessed sin, which proves over and over again to be so devastating and destructive.

I know I’m not alone. We all run from God, but His love never changes, and it never fails. My desire is for you to come to know this same love.

May God Bless you until next time!